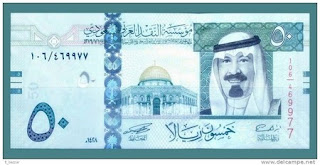

The rise of Mohammed bin Salman: A mixed blessing?

By James M. Dorsey

Saudi King Salman’s appointment of his son, Mohammed bin

Salman, as crown prince at the expense of his nephew, Mohammed bin Nayef, could

prove to be a mixed blessing for a kingdom in transition that faces significant

international challenges of its own making.

Prince Mohammed’s ascendancy was never in doubt. It was a

question of when rather than if. Reportedly ill and clearly feeble in his

public appearances, King Salman may have wanted to ensure sooner than later

that his 31-year old son would be his successor.

In doing so, King Salman appears to be taking a gamble.

Prince Mohammed has garnered popularity among Saudi youth, many of who feel

that his ascendancy puts in office a member of the ruling Al Saud family who

because of his age is more attuned to their aspirations.

The prince has introduced, to the chagrin of religious

ultraconservatives, entertainment, including music concerts, theatrical

productions, film showings and comedy performances, in a country in which

culture was largely limited to traditional, religious and tribal expressions.

He has also signalled his support in principle for lifting the ban on women’s driving

and other rollbacks of austere public codes.

The prince’s more liberal vision, part of a far broader

process of change, comes, however, with a heavy price tag. Forced to

restructure the kingdom’s rentier economy at a time of reduced energy prices

and upgrade the country’s autocracy, Prince Mohammed’s measures sparked

criticism not only from the kingdom’s Sunni Muslim ultra-conservative religious

establishment, a pillar of the rule of the Al Sauds, but also ordinary Saudis

who have felt the cost of change in their wallet.

The significant revamp set out in Prince Mohammed’s Vision

2030 plan for the future involves a unilateral rewriting of the kingdom’s

social contract that offered a cradle-to-grave welfare state in exchange for

political fealty and acceptance of Sunni ultra-conservatism’s austere moral and

social codes.

Saudis have, since the introduction of cost-cutting and

revenue-raising measures, seen significant rises in utility prices and greater

job uncertainty as the government sought to prune its bloated bureaucracy and

encourage private sector employment. Slashes in housing, vacation and sickness benefits

reduced salaries in the public sector, the country’s largest employer, by up to

a third.

Online protests, fuelled in part by Prince Mohammed’s

acquisition of a $500 million yacht shortly after he came to office, persuaded

the government in April to roll back some of the austerity measures and restore

most of the perks enjoyed by government employees.

Reduced public spending and delays in payments have put two

of the kingdom’s major companies, Bin Laden and Saudi Oger, in dire straits. Thousands

of employees have been unpaid for months. Bin Laden workers last year burnt a

bus in Mecca in protest. Oger reportedly is bankrupt and likely to go into

liquidation.

On the foreign policy front, Prince Mohammed, since first

coming to office in 2015, has embroiled Saudi Arabia in two major international

entanglements without an exit strategy, forcing the kingdom to grope for a face

saving way out.

Prince Mohammed also serves as defense minister and is the

lead official responsible for the war in Yemen. Three years into the war, Saudi

Arabia’s ability to effectively deploy its massive state-of the-art military

acquisitions is in question. The war has dragged on producing a humanitarian

crisis with large numbers of people on the verge of starvation and risks of epidemics

as evident in a recent outbreak of cholera. The crisis has caused Saudi Arabia

reputational damage and promises to produce a generation of Yemenis who will

resent the suffering and destruction caused by the ill-fated invasion.

Similarly, the diplomatic and economic boycott of Qatar,

initiated by Prince Mohammed and his UAE counterpart, Mohammed bin Zayed, threatens

to backfire. The ability of Qatar, a tiny state with only 300,000 citizens, to

resist the embargo and the inability of Saudi Arabia and the UAE to put forward

demands that stand a chance of garnering international support has turned into

an embarrassment.

The US State Department took the two Gulf powers to task

this week. State Department spokeswoman Heather Nauert said in the strongest US

language yet, that “now that it has been more than two weeks since the embargo

started, we are mystified that the Gulf States have not released to the public,

nor to the Qataris, the details about the claims that they are making toward

Qatar. The more that time goes by the more doubt is raised about the actions

taken by Saudi Arabia and the UAE.”

Ms. Nauert’s comments followed a series of US steps that

appeared to strengthen Qatar in its dispute with Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

Those steps included a joint US-Qatari naval exercise, a $12 billion fighter

jet deal, and a statement by US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson that

designation of the Muslim Brotherhood as a terrorist organization, a key demand

floated by Saudi Arabia and the UAE, was all but impossible.

Prince Mohammed, moreover, has failed to win substantial

support in the Muslim world for the Saudi-UAE campaign. Most major Muslim

nations, including Pakistan, Bangladesh, Indonesia and Malaysia are keen to

stay on the side lines. Turkey is supplying Qatar with food and has sent troops

to the Gulf state.

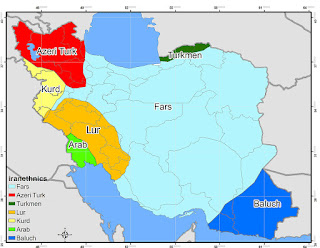

On a third front, tension with Iran has escalated since

Prince Mohammed’s rise. The prince last month poured fuel on the fire by portraying

the conflict between the two Middle Eastern rivals in sectarian rather national

or ideological terms and promising to take the fight to Iran itself. At least, regarding

Iran, Prince Mohammed enjoys the support of the United States even if, like in

the case of Qatar, much of the Muslim world does not want to be sucked into the

dispute.

Prince Mohammed has his work cut out for him. To succeed in

turning the Saudi economy around, blunting the sharp ends of Sunni Muslim ultra-conservatism,

and bringing the kingdom’s autocracy into the 21st century, Prince

Mohammed will have to demonstrate the kind of deftness and ability to build bridges

he has yet to put on display. While bold in his ambitions and willingness to

gamble, he will also need to recognize the need for exit strategies.

Prince Mohammed could well prove to be the figure that

pushes through the kind of change that will enable Saudi Arabia to successfully

compete in the 21st century. By the same token, he could also tie

the kingdom further into knots.

Dr. James M. Dorsey is a senior fellow at the S.

Rajaratnam School of International Studies, co-director of the University of

Würzburg’s Institute for Fan Culture, and the author of The Turbulent World

of Middle East Soccer blog, a book with

the same title, Comparative Political Transitions

between Southeast Asia and the Middle East and North Africa, co-authored with Dr.

Teresita Cruz-Del Rosario and three forthcoming books, Shifting

Sands, Essays on Sports and Politics in the Middle East and North Africa as

well as Creating Frankenstein: The Saudi Export of Ultra-conservatism and China

and the Middle East: Venturing into the Maelstrom.

Comments

Post a Comment